“Nobody enjoys sitting on a stoop or looking out a window at an empty street."

It’s an understatement to say that the recovery of America’s downtowns after COVID has been uneven. Newly released research tracked mobility data for 66 U.S. and Canadian metros between March and June 2023, benchmarking foot traffic against the same period in 2019. The mean recovery rate is 76% but the spread is what’s telling: Las Vegas recovered to 102%, while St. Louis sat at 53%. This wide dispersion signals that urban recovery is now shaped by structural, not cyclical, forces. And now we’re starting to learn what’s behind the uneven rebounds.1

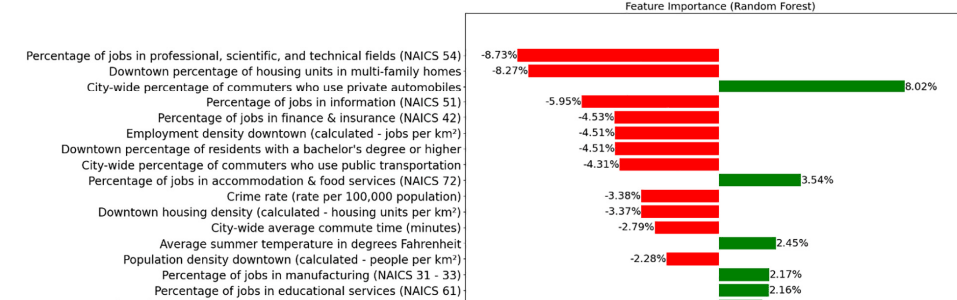

Employment concentrations matter most, a topic we’ve explored in earlier issues. The downtowns slowest to recover are in cities with jobs easiest to do remotely, notably professional jobs, and employees in technology, finance and insurance. Downtowns with high concentrations of these employees are recovered only 53% to 70%. This effectively caps near-term absorption potential for CBD office and slows recovery of surrounding retail and multifamily. Seattle, Minneapolis and San Francisco are good examples. These industry concentrations were the most impactful of all characteristics tested, and unfortunately they were headwinds to recovery.

Downtowns performed better when their workforce included employees who could not easily work from home. Hospitality, food service, manufacturing and educational services are good examples, and these four sectors alone came with significant recovery tailwinds for cities and “accounted for almost 8% of the total predictive capability of the model.” These industries helped push Las Vegas to the No. 1 spot. Bakersfield, CA, with its base of healthcare, education and hospitality, also did well, recovering to 95% of its 2019 level.

Other headwinds and tailwinds to downtown recoveries were not as easy to guess. Of all the characteristics that predicted recovery, the single greatest catalyst is a population where people commute by car rather than public transportation. This stands in contrast to a long-standing assumption (or wish?) that transit-oriented downtowns are inherently more resilient. During the pandemic an aversion to public transportation made sense, but by 2023 that was no longer a factor, and the authors were unable to explain this finding. They did report that longer commute times slowed downtown recoveries, which is more intuitive.

The survey compared downtown recovery rates against “51 explanatory variables,” including employment concentrations, socio-economic factors, commuting trends, crime rates, weather and more. The authors acknowledge some factors were not tested, homelessness and residential rental rates being two important ones.

Other important determinants included crime, as measured prior to the pandemic, which drove slower recoveries. Density also played a role: population density, employment density and housing density all correlated with weaker recoveries. Cities with colder weather recovered more slowly as well. Education level, usually high on the list of metrics cities want to brag about, in this case correlated negatively with downtown recoveries. In fact it’s fair to say that affluent, white-collar populations appear to have structurally rewritten their relationship to downtown, reshaping demand curves accordingly.

See the magnitude of certain characteristics’ impacts on recovery in the graph below:

The authors also compared select downtown recovery rates in big American cities with the recovery rate of the full MSA excluding downtown. The results indicate a significant bias toward the “donut” submarkets adjacent to–but distinct from–the CBDs.

And here’s how much each city in the study recovered:

It’s worth noting that “recovery” can be hard to measure: is unemployment the most important metric? Or business closures, or maybe consumer spending or leisure travel? The authors used cell-phone-based mobility data, as prior studies have found correlations between the number of visitors to city areas and “GDP, consumer spending and spending-related statistics.”

This suggests that more people downtown has a strong link to “revitalization of the urban environment.” But these relationships are correlational, not causal, and the findings are one or two degrees removed from direct drivers of real estate value. The key insight here isn’t about winners or losers; it’s about direction. From 2000 to 2020, investors were rewarded for betting on urbanization and density. Post-COVID, those bets look exhausted and upside-down.

If the last cycle rewarded density, the next one is likely to reward dispersion: nodes over cores, convenience over concentration. It’s the cross-current running through today’s urban recovery story.

Special thanks to the Burns School of Real Estate at the University of Denver for their support of the Haystack.

The Rake

Three good articles.

Apartment sales dropped 28% in October - Multifamily Dive

Despite a 28% drop in October sales volume driven by a lack of forced selling, Multifamily pricing rose 0.5% year over year, while cap rates fell 10 basis points to an average of 5.5%.

After navigating a major pricing reset, Commercial Real Estate is shifting toward optimism for 2026 as Class A office scarcity and receding new supply in multifamily improve the outlook.

The DOJ's measured RealPage settlement creates a critical precedent by restricting the use of nonpublic competitor data in algorithmic rent setting, increasing data governance focus.

The Harvesters

Someone making real estate interesting. They don't pay us for this, unfortunately.

Who: Sunday

What: Can you finally get some good help? Memo the robot, coming to a kitchen (very) near you.

The Sparkle: Memo is said to autonomously clear tables, load dishwashers, fold laundry, make coffee, and more. This thing can fold socks together and make espresso. The company just emerged from stealth after more than a year, building the robot on an AI foundation of continuous learning. The Haystack also wants to be part of the demo–purely to ensure the “and more” features reach their potential, specifically mixing drinks, making guacamole and handling basic home repairs.

From the Back Forty

A little of what’s out there.

Social scientists are always coming up with fresh ways to understand how people perceive others, and recent studies tend to focus on our increasing tendency towards distrust and even acrimony. One study on the decrease in social trust found that financial concerns, job losses and lower confidence in political institutions were driving an overall decline in social trust.

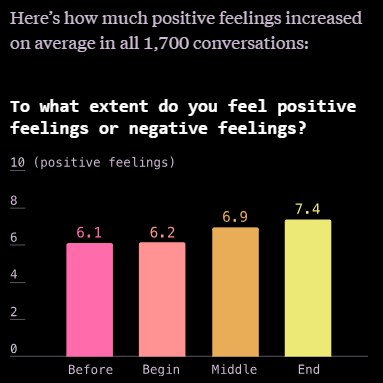

One study put pairs of strangers together, each for half an hour and entirely without structure. Participants reported on how they felt before, during and after the conversation. Prior to talking, people assumed they would not like the other person. Look what happened, and click the link for a fantastic visual walk-through of the experiment.

Thank You To Our Sponsors

Editor’s Note: The Real Estate Haystack believes in sharing valuable information. If you enjoyed this week's newsletter, subscribe for regular delivery and forward it to a friend or colleague who might find it useful. It's a quick and easy way to spread the word.

1 Forouhar, A., Chapple, K., Allen, J., Jeong, B., & Greenberg, J. (2024). Assessing downtown recovery rates and determinants in North American cities after the COVID-19 pandemic. Urban Studies, 62(6), 1209-1231. https://doi.org/10.1177/00420980241270987 (Original work published 2025)