“Productivity isn't everything, but, in the long run, it is almost everything. A country’s ability to improve its standard of living over time depends almost entirely on its ability to raise its output per worker."

Economic progress often hides in plain sight. We see it when prices fall or tasks that once took a day now take a minute. Over time these gains compound, reshaping how we live and what we can afford. But the opposite is possible; some industries grow more expensive and less efficient even as everything around it improves. When one of those industries sits at the center of housing supply, inflation, and economic growth, the consequences are serious.

Thinking about it from the 50,000-foot level, economic growth is a function of two simple inputs: how many hours people work and how productive they are during those hours. Historically, workers on average have become much more productive, driving the inflation-adjusted cost of goods down and allowing for greater specialization of labor, which has a reinforcing effect on productivity growth. Rich or poor, we all benefits from a century of extraordinary productivity growth.

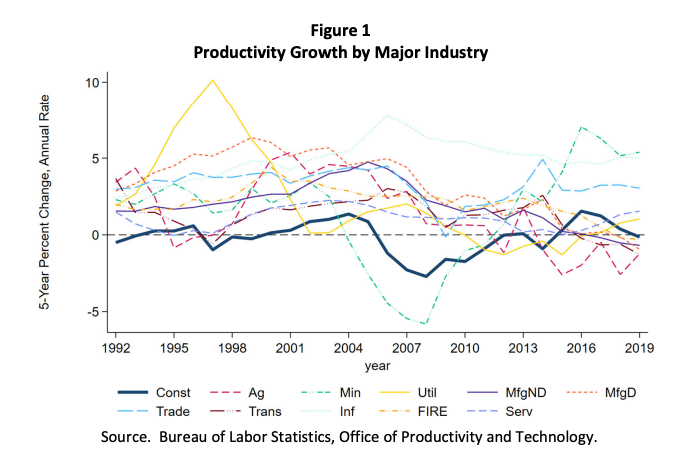

This growth -- which is robust and consistent across so many economic categories, as shown in the graph below -- has eluded the construction industry entirely. Since the Bureau of Labor Statistics started tracking productivity in 1987, construction has averaged negative growth from that year to 2019. Yep, negative. Even assuming zero inflation, workers were building buildings and houses for less money in 1987 than they are today.

Click to enlarge

You can see evidence of low productivity growth in many places, including single-family construction: “The average length of time from start to completion of single-family homes increased from 6.2 months in the mid-1980s to 7.0 months in 2019.”

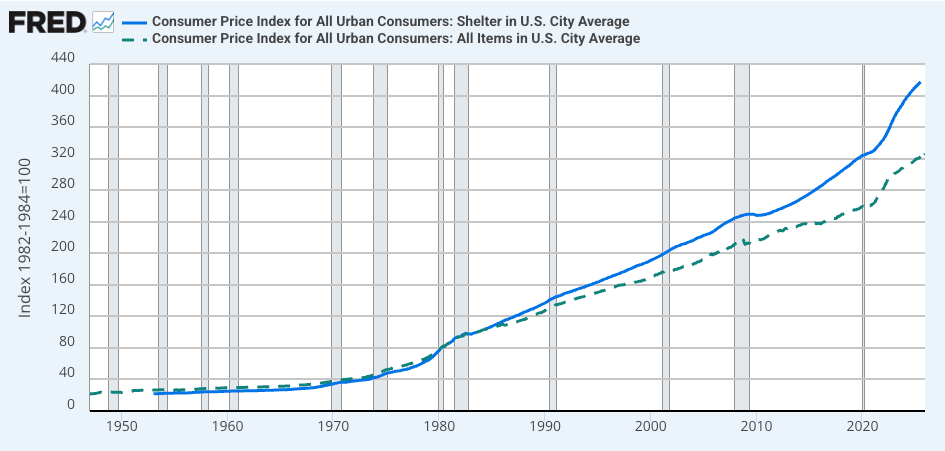

It matters that we keep getting worse at building. We rely on this industry to build for-rent and for-sale housing, and we’re short to the tune of 2.5 million to more than 5.0 million units, according to J.P. Morgan. Shelter costs also make up more than one-third of the consumer price index. And they (blue line below) have been outpacing overall inflation (green dashed line) for more than 45 years.

Click to enlarge

Given the massive societal impacts, construction’s productivity problems have been the subject of renewed research, and one recent paper took a fresh look at this trend to see if it’s not as bad as it seems, and to start to understand the drivers of this unfortunate trend.1

The researcher’s initial skepticism was intuitive: Negative productivity growth over more than 30 years, really?? This trend “sounds implausible,” they noted, given innovations even lay people know about, like better design technology, and basic technological progress like nail guns.

That skepticism has merit. Sometimes the calculations are problematic. Construction productivity is measured essentially as the number of structures built divided by the cost to build them. But not all structures are equal. Over time, buildings have improved in ways the metric doesn’t capture: better energy efficiency, more structural integrity, better quality roofs, countertops and other finishes, etc. The productivity measurement does not take many of these characteristics into account.

After a deep analysis into many sources of potential “bias” related to unmeasured improvements, the researchers concluded that this was not a large factor, and that productivity growth “has indeed been quite low.” Unobserved improvements in quality may have pushed the cost of construction up no more than 0.5-percentage-point per year, with “generous assumptions” inherent in that analysis to establish a likely maximum potential amount.

That means even giving credit for unmeasured output improvements, the authors write, “we estimate that productivity was essentially flat in the construction sector from 1987 to 2019.” Labor-saving innovations have not kept pace with other factors that increased the costs of construction. This is truly a massive underperformer vs. other industries.

There’s been little academic investigation into the “Why?” behind this trend. The researchers took a crack at it, starting with single-family construction, in part because that data is more readily available vs. commercial construction. The worst-performing states “experienced productivity declines of about -4 percent per year” while the best performers saw “productivity growth of about 1 percent per year.” About 80% of states had productivity growth at or below zero.

States with the weakest productivity growth included Massachusetts, New York and California. The strongest? West Virginia, South Carolina and Montana. The common thread: States and metro areas with greater land use regulations saw much less productivity growth. This was “one of the main findings” of the work.

Regulation took several forms. Delays in permit approval were “most strongly and robustly correlated with [negative] productivity growth.” Supply restrictions like a cap on total issuable permits or limits on the size and density of multifamily buildings also were negatively correlated to productivity growth.

Impact fees also mattered. As did areas “where a large number of local entities” were needed to approve a project. All of these were bad for productivity. Interestingly, growth was not related to the population or density of an MSA. Big cities can get better at building.

Overall, the findings suggest that this isn’t a story about a single hapless industry. It’s a case study in how political and governmental decisions can shape real economic outcomes, quietly compounding for decades. Basic land use rules and processes don’t just change where or what gets built, they change how efficiently an entire sector operates. When construction productivity stalls, housing gets scarcer, shelter costs rise, inflation stays stickier, and labor becomes less mobile.

This is what makes construction’s productivity problem different from most regulatory failures. There is no small, easily identifiable group of losers. Everyone pays, slowly and persistently, through higher housing costs and weaker real growth. The uncomfortable implication is that even well-intentioned local policies can accumulate into a national economic problem. Productivity growth isn’t just about technology or innovation; it’s also about whether our institutions allow those gains to show up in the real world. Here, the evidence suggests they often don’t.

Special thanks to the Burns School of Real Estate at the University of Denver for their support of the Haystack.

The Rake

Three good articles.

Office Investment Outlook Strengthens for 2026 - CRE Daily

While the office sector remains bifurcated, 2026 marks an entry point for opportunistic capital as stabilized valuations and a flight to quality begin to unlock high-conviction deal flow.

Two Housing Markets, One Economy - Globe St.

As the U.S. housing market bifurcates, institutional investors face a stark divide between resilient, undersupplied metros and regions grappling with affordability ceilings and inventory overhang.

As American retail store anchors fade, private clubs are taking over more commercial real estate - CNBC

Institutional capital is increasingly backfilling big-box vacancies with high-margin private clubs, pivoting away from traditional retail toward "experiential" assets with stickier, membership-driven cash flows.

The Harvesters

Someone making real estate interesting. They don't pay us for this, unfortunately.

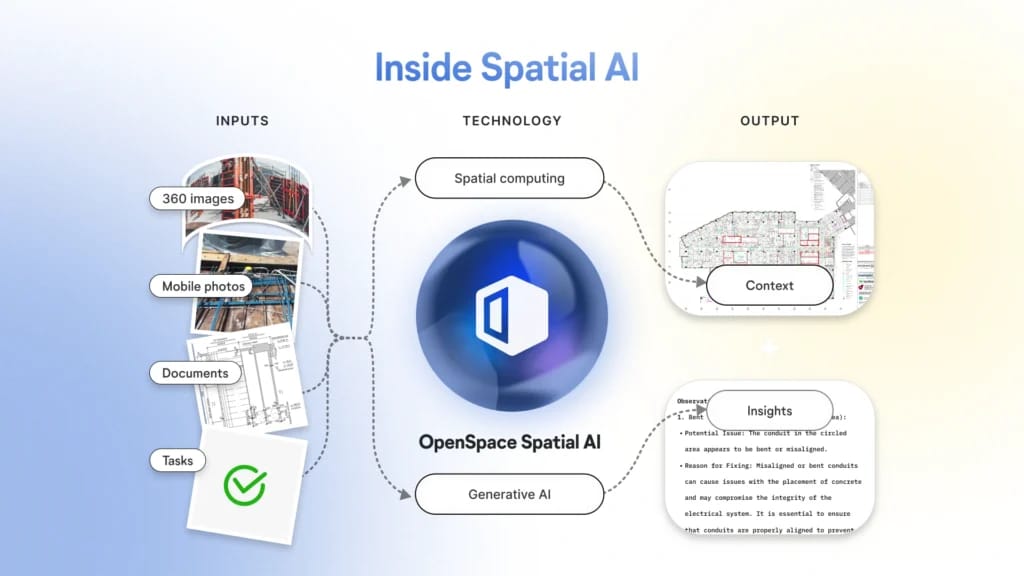

Who: OpenSpace

What: Uses passive image capture and computer vision to document construction progress and surface schedule risk in real time.

The Sparkle: OpenSpace doesn’t promise to “revolutionize construction.” It does something much more valuable: it reduces friction, rework, and finger-pointing. Owners, lenders, and GCs get a shared, objective record of what was built, when, and where—without adding labor to the jobsite.

That changes behavior.

Issues get caught earlier, disputes get resolved faster, and site visits become about decisions instead of discovery. The quiet tell is adoption: once a sophisticated owner or GC uses OpenSpace on a complex project, they tend to mandate it on the next one. In an industry where delays compound and accountability is diffuse, that kind of institutional stickiness is rare—and meaningful.

From the Back Forty

A little of what’s out there.

Ravens, known for their intelligence, mimic wolf howls to attract wolves to potential prey. After the wolves make a kill and tear open the carcass, the ravens swoop in to steal scraps. This symbiotic relationship even extends to ravens leading wolves to food sources, showcasing a rare interspecies partnership built on mutual benefit.

Thank You To Our Sponsors

Editor’s Note: The Real Estate Haystack believes in sharing valuable information. If you enjoyed this week's newsletter, subscribe for regular delivery and forward it to a friend or colleague who might find it useful. It's a quick and easy way to spread the word.

1 Daniel Garcia, Raven Molloy, Reexamining lackluster productivity growth in construction, Regional Science and Urban Economics, Volume 113, 2025,104107, ISSN 0166-0462, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.regsciurbeco.2025.104107