“Discovery consists of seeing what everybody has seen and thinking what nobody has thought."

Uncertainty in the office market continues as the national vacancy rate approaches 21%, a figure that may understate the true underlying weakness in near-term office utilization and demand. But, despite the gloomy trends and investors’ fears about the sector, it’s clearly not dead. Occupancy didn’t collapse to 50%, or even 70%. In fact, for stronger office REITs, both operating income and average occupancy are on the rise, according to Moody’s.

Active and prospective office investors thinking about the right approach to the sector could benefit from a mindset shift related to a deceptively simple question: “How is office space priced?” New research has found the office market is segmented “based on leases’ space size (square footage),” and that spaces of a commonly found size within a market command a rent premium.1 In fact, if a specific size is abundant—meaning it represents a higher share of all available spaces in a market—that size tends to earn significantly higher rents. The authors call this the “Abundance Premium.”

At first glance, this concept sounds counter-intuitive, and “Abundance Premium” might even be a paradox. If a market has many 10,000sf office spaces, logic suggests rents should fall due to oversupply. Not so: A core finding of the research is that the space market accurately reflects but under-accommodates demand in an MSA, leading to the Abundance Premium. Basically, you can slice up an office market by lease size (square feet), and each slice is “likely to face different demand and supply.”

The authors found robust evidence of an Abundance Premium: overall, if an Abundance factor increases by ten percentage points, monthly net rent rises $0.15psf ($1.80 annually). That’s a lot! It was strongest in the Eastern markets (NYC, DC) at $0.22psf, weaker in the West (SF, Dallas, LA) at $0.08 and generally consistent throughout the period of the study.

Data for the research - what today is a working paper - covered those five largest office markets from 2010 to 2019, analyzing nearly 61,000 Class A leases. To determine “similar” space sizes, the authors grouped leases within ±10% of each other in square footage—a practical but admittedly ad hoc method. More sophisticated clustering techniques could refine the analysis.

To calculate Abundance, the authors counted the number of leases in a market with “similar” sizes and divided by the total number of leases. A lease with an Abundance factor of 3% means that 3% of all leases in that market are for a similar size.

Indexed distribution of office-lease-sizes in LA, SF, Dallas, DC and NYC; the black graph is the five-market average

The Abundance Premium was robust across geography and time. It wasn't driven by tenant industry mix or concentrated industries in the MSA. The research also tested the lease-size-based Abundance Premium (which as noted they found great evidence for) against the possibility of a lease-term-based Abundance Premium (which they found zero evidence for).

Digging deeper, the Abundance Premium tends to be larger for larger spaces. This logic tracks: Smaller spaces can be carved out of larger ones, giving landlords flexibility to accommodate small-space demand. But it’s harder to aggregate smaller spaces into larger ones, so rents for large-format spaces tend to command more of a premium.

The Abundance Premium also increases as building size increases. Causation here was not clear. The authors speculate that larger buildings can offer more spaces in high-demand (“congested”) size segments. But we weren’t so sure. Larger buildings also tend to have other rent drivers: view premiums, more capital for amenities or simply a more prestigious address.

It’s important to emphasize that this study’s data set ends in 2019, just before Covid sent the office market spiraling, and in the January 2025 working-paper draft the researchers acknowledge those “dramatic changes” in the office market. Our recent article on WFH trends illustrates how office demand is probably shrinking, not growing.

Although we don’t know if the specific Abundance Premium figures they found are still applicable now, there’s no reason to suggest the concept does not apply. In fact much of the value of this paper is to highlight that there’s really no such thing as an ‘office building’ in the minds of customers, only office spaces, and real estate investors should approach these assets each as a collection of spaces with specific sizes competing in different demand pools. The authors imply their own similar belief regardless of Covid: “We believe [this] is a fundamental relationship that reflects the effects of demand and supply on rents.”

Our experienced, but minimally academic, view is that an Abundance Premium still exists post-Covid; there are still clusters of high demand based on size. But likely all of the relevant metrics have decreased. Meaning there’s less overall office demand so less demand in those high-demand Abundance clusters, and maybe less of a rent premium. Think of it as the demand curve shifting to the left.

Regardless, the core finding in this research raises questions about space-size-based premiums in other real estate product types, notably industrial and retail. Industrial space, which within its subsectors is a near-perfect commodity product, is begging to be analyzed for an Abundance Premium. Like with office, developers and investors would clamour for a data-backed way to more-precisely demise and market their spaces, especially given how easy it is to reconfigure industrial buildings.

Retail would be an interesting and less intuitive case study. Submarket and specific location matter: a retailer in one neighborhood can well outperform a similarly sized location across town. While that’s true from the idiosyncratic perspective of a specific retailer, if you zoom out and consider an MSA overall, an Abundance Premium for retail based on size is still very possible. Inquiring minds want to know.

Bottom line, real estate as an industry and culture sees its origins in finance, and thus is sophisticated as an investment discipline, but it often lacks a customer-centric perspective (hospitality excluded). This paper considers the same office markets we’ve all been studying for years, but by shifting to a demand-side perspective (i.e. customer), it uncovers insights that feel fresh and useful.

The Rake

Three good articles.

Brookfield's new real estate chief foresees a market normalization with "mega-deals" making a comeback, evidenced by the firm's significant $13 billion in property sales this year. They're strategically acquiring prime assets like data centers and rental housing.

A new bipartisan housing affordability bill, the ROAD to Housing Act of 2025, is advancing in Congress. It aims to boost supply by tackling zoning barriers and incentivizing development in areas like opportunity zones, signaling significant shifts for real estate investment strategies.

Industrial saw a significant recalibration in Q2 2025, with warehouse vacancy rates rising to an 11-year high as new supply outpaced slowing absorption. Investment volume contracted sharply, though rent growth remains positive.

The Harvesters

Someone making real estate interesting. They don't pay us for this, unfortunately.

Who: Little Houses Group

What: Nope, not tiny homes. London-based LHG operates family-oriented urban membership clubs. Earlier this year they raised capital from Blackstone for expansion.

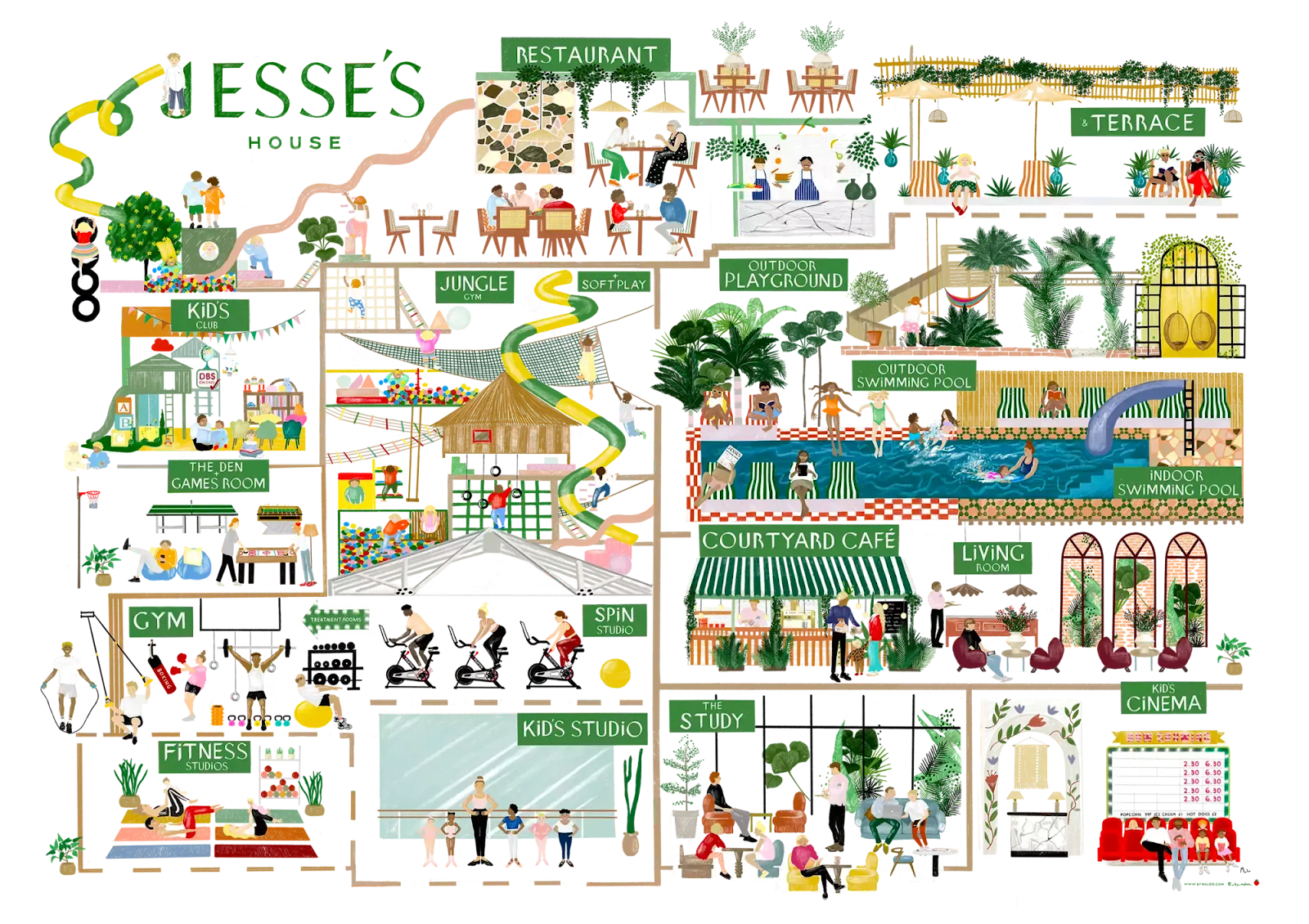

The Sparkle: Chasing what could be a very sticky demographic, LHG “Houses” have high-design spaces for adults and young children. Think restaurant, cafe, gym and studio (with classes), library and co-working space for the grown-ups, nursery, jungle gym room and other well-thought-through indoor and outdoor play spaces (also with plenty of daily programming) for kids. They have two locations with more coming (and fast followers like Little Big Hospitality setting up similar offerings in the U.S.). Check out this “site plan” for one of their Houses:

From the Back Forty

A little of what’s out there.

For those who love placemaking and generational real estate…

The Grand Bazaar in Istanbul is a living testament to centuries of commerce, craftsmanship, and cultural exchange—a city within a city, and one of the world’s oldest and largest covered markets. Commissioned in 1453, its original purpose was to centralize trade in clothing and jewels, and to generate income for the Hagia Sophia. Over time, it expanded into a sprawling labyrinth of 60+ streets and nearly 5,000 shops, attracting between 250,000 and 400,000 visitors daily.

Step inside, and the rhythms of centuries past still echo—vaulted ceilings, stone corridors, hand-lettered signage. Merchants call out to passersby as they have for generations. The space isn't just old—it’s alive, economically and culturally.

Thank You To Our Sponsors

Editor’s Note: The Real Estate Haystack believes in sharing valuable information. If you enjoyed this week's newsletter, subscribe for regular delivery and forward it to a friend or colleague who might find it useful. It's a quick and easy way to spread the word.

Office Space Segmentation and the Abundance Premium, working paper by Liang Peng and and Xue Xiao, January 2025, link to paper: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=5127568